Sports

A year ago, Sha’Carri Richardson boldly said, “I’m not back, I’m better,” after winning the 100-meter U.S. title and going on to win the world championship. This set the stage for her own comeback tale.

As she prepares to compete in her first Olympics, new queries have emerged: Can she still outperform a group of the world’s fastest women? Can she withstand the extra pressure that comes with being an Olympic athlete?

The 24-year-old frontrunner in the women’s 100-meter Olympic event has been transparent and honest about her journey to become a more conscious, appreciative version of herself. Her unfavourable introduction to the world at the 2021 U.S. Olympic trials stemmed from a positive marijuana test.

But she has revealed very little about what transpired in the three years that have elapsed between her breathtaking fall and her motivational return. Regarding her biological mother’s passing and the depressive episode that followed, she has left hints.

With all of this mystery, upheaval, and eventual success, Richardson has become legendary and her fervent and expanding fan following is clamouring for more. On social media, some people are really interested in the fingernails and haircut she will be running with.

She is now more than just a well-known sprinter thanks to it. Her suspension sparked debates over drugs, anti-doping laws, racism, and the Olympic system, which is still predominately controlled (and covered) by older, white men. She is a well-known, young Black lady.

Richardson stated, “Being well-known is not my aim.” But one thing is for sure—I don’t want to be recognised for it. Nobody does. Being the best version of myself is crucial to me in all the areas that I value, including my work, community, and family.”

How Richardson communicates with media

This realisation resulted from the two questions Richardson consented to respond to from The Associated Press as a condition of her Powerade sponsorship. Over the course of the last year or more, she has accepted these kinds of brand-placement trade-offs in many of her interviews.

Other hints have been provided by her on social media, where she has openly discussed her mental health problems and her thoughts of suicide as a teenager, all the while giving others hope.

There were traces of the rift between Richardson and the media from last year’s worlds. Scenes from her heated conversations with reporters were featured in the “SPRINT” behind-the-scenes Netflix series.

“I feel like every move I make, there’s a lot of noise about it in the media,” she remarked in the documentary, reflecting on the role the media played in narrating her tale. You give and you receive in equal measure. Well, that is just my opinion.

Her sporadic in-person interviews with media this year have been less contentious, especially at the U.S. Olympic trials when she won her second consecutive national title in June. Her remarks focused on several incarnations of the same theme: family, responsibility, and personal development.

“I would say in the past few years, I’ve grown to have a better understanding of myself,” Richardson said. “I have a deeper respect and appreciation for the role I have in the sport, as well as my responsibility to the people who believe and support me.”

Grandmother has guided her

Richardson’s polite online interview with Vogue last summer, where she mentioned that she did not talk about her biological mother or the drug test, was the closest she got to talking about the suffering she went through as a youngster.

“I owe it all to that strong, wise Black woman who reared me,” the woman remarked, referring to her grandmother Betty Harp, who frequently sits trackside during Richardson’s biggest races. “Everything. I consider myself fortunate to have encountered other individuals who have supported and assisted me in my life. But she is the foundation.”

Richardson still has a lot of time to grow as a public personality and athlete. It takes some sprinters until their late 20s to reach their prime.

The harsh reality is that securing a gold medal is the primary means of leaving a lasting impression on the public for any athlete participating in a sport that does not make news outside of Olympic years.

The favourite

All indications lead to Richardson winning the Olympic 100 final at the Stade de France on August 3.

In 10.71 seconds, she won the Olympic trials, setting a new world record for this year. Shericka Jackson of Jamaica, one of her primary rivals, seemed weak in a tune-up race earlier this month, raising doubts about her preparedness for the Olympics.

The Shelly-Ann Fraser of JamaicaRichardson is trailed by Pryce by four Olympics and eight Olympic medals. On the largest stage in the sport, experience counts, but will it be sufficient to overcome Richardson’s unparalleled pace in 2024?

Sprint legend Michael Johnson once observed, “As an athlete, when you know you’ve got the talent and all eyes are on you, it’s tough.” It becomes a tremendous relief when you “really prove to yourself and the world that, hey, I can do this,” which may pave the way for her to achieve even greater success.

Comeback has made her a star

Though Richardson hasn’t quite won yet, there’s still the gold medal to be won.

Because of her Nike shoe contract, her visage was all over Eugene, Oregon, during the Olympic trials. She has consistently appeared in NBC’s Olympic marketing.

Richardson may not be the Simone Biles of these Olympics, but there won’t be another interesting figure when gymnastics is done and the focus shifts to the track.

Olympic gold medallist Sanya Richards-Ross, who covers track for NBC, stated, “The entire world was involved and got caught up in the magic of who Sha’Carri is.” “And we’ve had an amazing chance to see her develop and mature as she handles all of it. Seeing her today, embodying what it means to be the face of the sprints, has been breathtaking. It has several accessories.”

A work in progress

As good as Richardson was in the 100, there was a hint of sadness when she placed fourth in the 200, the race in which she won the bronze medal at the previous year’s world championship. As a result, she will not have the opportunity to capture the coveted sprint double, as Noah Lyles will on the men’s side.

However, Richardson’s very first race that week—a preliminary heat of the 100—might have been the one that most encapsulated everything about her as an athlete. She had to catch up to win since she stammered off the starting block and almost slipped out of her lane.

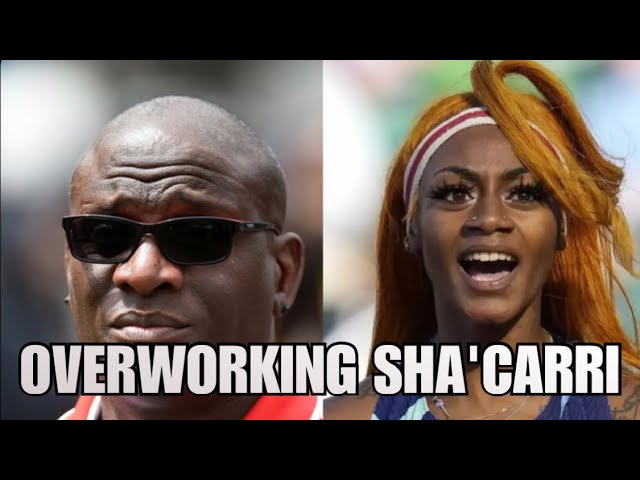

She was the first to acknowledge in her succinct post-race remarks that she is far from a finished product and is still working hard to improve every day under the strict supervision of her coach, Dennis Mitchell.

Everyone didn’t realise Richardson had raced that 100 in 10.88 seconds with her right shoelace unfastened until she crossed the finish line.

There she was, then: flawed, a work in progress, an enigmatic racer who was still blazing her own trail and taking the lead because, at the end of the day, she was still quicker than everyone else.